My father died in May, seven years after my mother. We are slowly emptying the house the two of them lived in together since the autumn of 1966, a couple of months after I was born.

My father died in May, seven years after my mother. We are slowly emptying the house the two of them lived in together since the autumn of 1966, a couple of months after I was born.

The house contains my childhood, of course, and those of my older brother and sisters – but mostly now it embodies my parents’ lives together, the choices they made, together or singly, the things they loved, the things they could afford, the things they could not afford but bought anyway, good furniture followed by worse once children required accounting for, my mother’s resilient DIY eventually supplanted by an old age of greater ease and comfort.

To break it up, this life, seems strangely disloyal. Should their choices and tastes mean so little to us? Do photographs, which we will keep, say more about them than the LPs they collected, the pictures and prints on the walls, the vases and lamps, the glasses and the linen?

People are fond of saying, in the social media age, that we are all curators of our own lives these days. But weren’t we always? Aren’t the undispersed houses of the dead always museums of a kind, suspended in time – because both finished and unfinished – in just the way Pompeii is? The ghosts that inhabit the homes of the lost are not merely those of the past – they are also the ghosts of the future, the lives unlived, the films unseen, the thoughts unarticulated, the food uneaten, the books unread.

Death ends our dialogues with the dead, but the conversations want to go on.

For me, that talk is almost always about the books.

The best books – the ones we carry with us always in our hearts – find the words for things that we feel within us already but cannot express – sometimes have not even known we wanted to express.

I look around at the packed shelves at my parents’ and think of all the emotions they contain. Perhaps I cannot capture how my mother felt on a given day one April or September, say. But I can know something of her in the words she read, in her radical’s surprise at the humanity of Queen Victoria’s letters to her children, or her profound identification with the Vera Brittan of Testament of Youth.

Every time I read the court martial scene in Catch-22, I can hear my father, wheezing and snorting with laughter as he read it out loud to us as children, tears of laughter – the only kind or tears I remember him shedding till the last years of life – slipping quickly down Saturday-stubbled cheeks, landing warm on my arm. He almost choked on it, too breathless with the absurd, savage logic of Heller’s humour to read at all.

But most of the books on my parents’ shelves resonate more quietly, words exchanged in distant rooms, things glimpsed behind us in a folding mirror. A good many I read myself as I grew up, often with my parents encouragement, occasionally their distaste; I don’t think Mum ever developed a liking for Ian Fleming, for example, although I find myself repeating even now her opinion that he wrote well, if not as well as his brother, Peter, despite the fact I have yet to read – or indeed see – even one of Peter’s books.

The galleries – museums, memory houses, what you will – those intimate spaces we curate in our own minds begin in our childhood reading as much as in our childhoods per se. For me the iconic Bond images aren’t Connery or Moore or Craig, but the covers of the 1960s Pan paperbacks that still sit on the shelves in the hall: the faux bullet holes in the cover of Thunderball; the scorpion clutching a pearl on You Only Live Twice; the blood-spattered snow of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

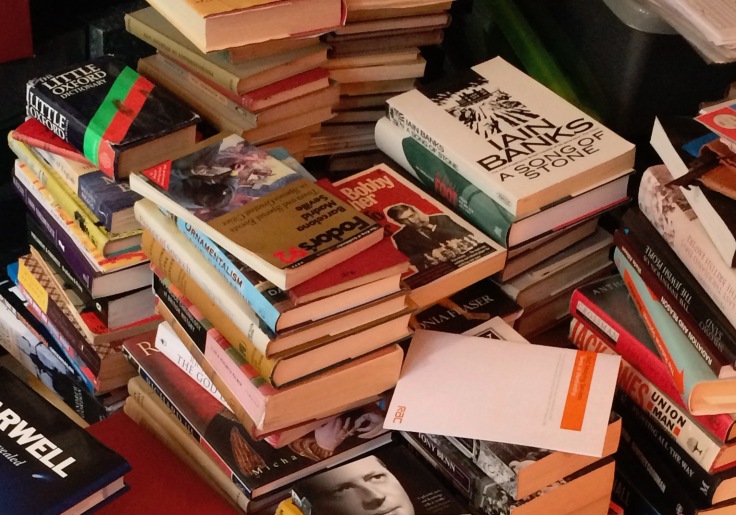

And so it is across every shelf. Many of the paperbacks’ brash colours have faded with sunlight and time. The hardbacks, stripped long ago of their jackets, have grown old too. They have not discoloured so much as acquired a patina of disuse; their bindings are stiff, their typesetting demodé. They smell tired, like baked dust.

Growing up, each book to me seemed to promise so much, each an unfamiliar world of its own wrapped inside the mystery of my parents’ hearts. Those I have never read still catch the eye, but this time with guilt: Eastern Approaches; Lust for Glory; Old Men Forget; The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists; Angel Pavement; The Man-Eater of Malgudi; and on and on. They are the among the earliest landscape of my life, I suppose; these enticingly unexamined vistas are somehow more evocative than the posters and prints that hung on the walls, like doors opened just a little onto shadowed gardens. The doors are still there; but to open them now would, I think, make my parents’ absence all the more painful.

These books stand for much of my parents’ emotional lives. For bookish people, that’s what books are. They aren’t mere stories or arguments or theses: they are aspirations. They are possibilities. They express the inquisitive longings of my parents: the kind of world they wanted to create for themselves and their children, of course. But it’s more than that. To buy a book is to express a desire. To want to think and feel something new; to see without seeing and know without knowing. Books fulfill us. To read a book is to open ourselves, to invite different lives into our own most private spaces. It follows that to leave a book unread behind us is its own kind of sadness: an opportunity stifled, a chance untaken.

I know there are many books here my parents never got round to reading. I can only guess at which. Each one seems to suggest a diminished life in a way, or poignant evidence of death’s broken continuities, the sense of lives not finished with, even though life itself has gone.

It is one of the strange qualities of books that the words they contain live for the reader as much as the writer – and they live for readers other than ourselves, too. We get a frisson – at least I do – when we hear someone speak about a book we know intimately ourselves – as if the depth and delicacy of our connection to the words it contains connects us to them also. The web of words vibrates a little and we feel it, the pressure of another person’s life, their thoughts and experiences humming through the threads and wires. So you heard it too, I think to myself. You understood the music that moved me so.

So much of my relationship with my parents was expressed through such connections. We lived through books. We exchanged them as gifts; we exchanged thoughts about them endlessly, books we had read, books we wanted to read, books we had read about. So to be in an empty house lined with shelves is to be in a library of lost conversations with them.

I look up at them, lined up beside each other, in no other order than that made by a random choice on a random day, subjects flitting erratically, seamlessly from one topic to another, book to book and shelf to shelf, the way intimate talk does when it seems to be endless.

I want to hold on to each one, but there are too many for my lifetime too.

Very deep, indeed!

Honest, and full of wisdom. Brilliant write.

Reblogged this on Jackie Garland.

Beautifully written.

I am the reader in my home, so you made me project what that process will be like for my family! Whoa, I think I’m going to tidy those shelves some more!

Regards.

I am sorry for your loss.

As I read this, I found words to so many emotions that I could never express in real life, the way I feel about books. Thank you for that

Great description ” slipping quickly down Saturday-stubbled cheeks” and thoughtful writing. I enjoyed the read.

This resonated for me even though my parents owned very few books and the ones they did were mostly my grandparents books – classics that were often Sunday School prizes from the early 1900s. Their own love of books was met by the public lending libraries so they avoided the expense of buying books. All my childhood reading was from the public library or school library and when I started to buy books as a student they thought I was mad. My wife is an obsessive reader and when we have periodic purges of the bookshelves to create space for the new I often mourn the loss of those books of hers that I didn’t get to read. The first blog I thought of curating would have been dedicated to those books I never read. I do wonder how my kids might respond to the loving and carefully assembled library that I will leave behind. Once I thought that at least they might be donated to a public library, but they are closing with such frequency that I doubt there will be any left.

Great post. Feel free to check out my page or share it.

Beautifully written

Music to my heart as your words are resonating still within me. Thank you for writing.

Well written. Books are indeed a closest thing to heart ♡ and it reveals a lot about a person.

This is so beautiful.

Reblogged this on Mild Granola Child and commented:

Wonderfully writing that strikes a chord with me. Mathew Lyons takes a beautiful journey through his parents’ book collection after they pass away.

Wonderful post on the timeless nature of books. I loved the part about buying a book as desiring- when we read a book, we perceive the fate of the narrator or character and suffer along with them, and rejoice that someone could indeed hear the sound we heard and articulate it better than we ever could. Like Descartes wrote, “the reading of all good books is like conversation with the finest men of past centuries.” Indeed, there are a hundred thousand conversations to be had, but never enough time to have them all..

This drills to a new level of deep. Really good work. Thanks for this.

I’m so happy that books mean so much to you, and you’ve been able to capture that perfectly. https://discoverlearnprogress.wordpress.com/

sorry about your father . Your feelings were beautifully said .

Beautiful

It’s amazing, totally inspiring

Very sensitively written. Touching. Thank you.

Nice article.

For the love of reading and the difference it makes… Beautiful!

Beautifully written, my father died leaving few possessions but many memories, which I wrote about early in my blogging. I still have imagined conversations with him. Thank you.

This was so much worth reading. Loved it. 🙂

我是个中文读者

Beautiful….

Very nice blog. Viewed the perfection of your relationship with your parents is niced.

quite the lovely and true sentiment. i totally understand those feelings as both my parents past years ago as well. those lost conversations you mentioned are all too common for me. i really enjoyed reading this.

That was great. Nicely penned down.

Be grateful. I pushed the last of my parent’s belongings off the back of a rented truck onto the waiting front-end loader one sunny day at the dump. They had no library. I did, and I do. Good luck, Lee

“It is one of the strange qualities of books that the words they contain live for the reader as much as the writer – and they live for readers other than ourselves, too. We get a frisson – at least I do – when we hear someone speak about a book we know intimately ourselves – as if the depth and delicacy of our connection to the words it contains connects us to them also…”

Thank you so much for your beautiful words. The image of shared books connecting us to others is a gift to those of us who are linked to loved ones through memory.

This is so beautiful.

Your post was filled my own fleeting thoughts, so many questions you voiced I somehow didn’t around to asking until 30 years too late.

Somehow my maternal grandfather’s method for selecting a book came to mind. He read page one, page 99, and the last page. I’ve got myself and never been disappointed.

This is so beautiful!

Do not have words to say how moving this post is.Brilliant.

I really like this passage

“To buy a book is to express a desire. To want to think and feel something new; to see without seeing and know without knowing. Books fulfill us. To read a book is to open ourselves, to invite different lives into our own most private spaces. It follows that to leave a book unread behind us is its own kind of sadness: an opportunity stifled, a chance untaken.”

I felt a slight chill when I red it..

It was well delivered.

It’a beautiful.

Such an homage. Took me back to emptying the house, 50 odd years full of life. My parents died within hours of each other on the same day, had been married 62 years, keepers of the flame and thousands of things that needed sorting through. Funny what resonates with you when it’s time to cull. Toni

http://wp.me/s84xvl-password

Hi ur post was awesome.. I request u all to refer to my blog too

Your upbringing, surrounded by books, is a gift. Lovely write.

Explains it all so well: the charm of books, and the oh so beautiful connection through them, with those we love. Brilliant.

An amazing piece to read. Pretty much connecting. All in all i love every bit of reading.

An excellent read. I am in love with books myself. And to converse about books, through books, is I think a rare connection that you seemed to have with your parents.

It’s beautiful, especially because I can relate to it so much. A house where books are shared can never be quiet even when there’s nobody there.

Thank you for writing this.

Beautifully written..loved it!

This was beautiful and rang all kinds of bells. My father was the historian Robert Blake and I found selling and breaking up his library worse than burying him. Something about his soul being in all those books and also on a more prosaic level he reviewed quite widely and tucked the reviews into each book. There’s an African proverb I love, ‘When an old man dies, a library burns down.’ That’s what it felt like.

It is so powerfully written. My grandmother passed away almost 36 years ago. But she has never faded away from our thoughts coz of her habit of reading to us the religious books. We

A testament to all things we hold dear…

Mathew, I’m sure your parents would appreciate the love and care you’ve taken to write this post in their honor, using the books that have bound you to them as your backdrop. And this astounding paragraph -:

“These books stand for much of my parents’ emotional lives. For bookish people, that’s what books are. They aren’t mere stories or arguments or theses: they are aspirations. They are possibilities. They express the inquisitive longings of my parents: the kind of world they wanted to create for themselves and their children, of course. But it’s more than that. To buy a book is to express a desire. To want to think and feel something new; to see without seeing and know without knowing. Books fulfill us. To read a book is to open ourselves, to invite different lives into our own most private spaces. It follows that to leave a book unread behind us is its own kind of sadness: an opportunity stifled, a chance untaken.”

– such a testament to all book-lovers. But what shines through the most is the respectful and loving way you see your parents as humans beings with hopes and desires, dreams and curiosities. May they Rest In Peace.

Such poetry and sharp emotion in your reminiscences. Thank you so much for sharing..

Brilliantly written!

this is indeed poignant. thanks gor sharing. personal writes are always the best. humans sharing their woes and aspirations to the world are beautiful people. they open themselves and hope for nothing back. they just want to be free.

may ur parents rest in peace.

Brilliant … beautiful … haunting. I grew up with my mother and older brother in a house of books. It was one of the primary ways we had of talking with each other and it took our minds off of the less pleasant aspects life. And now that I am older, I have become aware of the approach of the day when that conversation will cease and I will have to go through what you just did.

Thank you so much for this beautiful, insightful piece.

We (my siblings and I) did this exact thing with our parent’s possessions – it was hauntingly sad and for many of the reasons you describe so beautifully. Thank you for giving words to my thoughts.

Are we what we consume?

Reblogged this on Smile Circulation.

exquisite..

Mathew lyons’s The library of lost conversation,its nice, a different story I lovely enjoy it..

What a great post! My parents passed away as few years back and I remember going through those same emotions as I sorted through their stuff. So much of their belongings had emotional connections with me. I had a hard time even looking at some items for a few months. I felt like I was standing next to you as you described this experience.

Reblogged this on happy Friday world.

So beautifully articulated! Books do not merely transport the reader to another world, it holds within its leaves a plethora of memories and emotions which make the whole experience surreal. What better way than words to connect with the past, present and the future?!

Beautiful. It was like I was there.

Having a family that lives their lives enriched by the books they read is a priceless human experience. Thanks for evoking waves of gratitude with your post.

I really enjoyed reading this. I too am an “adult orphan” at 29 years old. I too have packed up bits and pieces of my parents’ lives and I too, am an avid reader, like my parents.

I love what you wrote about books being glimpses into one’s life as it is, as well as what it is hoped to be.

I treasure my moms copy of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet – complete with her name and maiden surname written by her own hand in the cover.

I wonder what will speak to my children when I am gone now that my books are encapsulated on a Kindle, photo albums reside on Facebook, and music is on a digital playlist. I suppose my clothing and home decor will be the only physical remnants of my presence. And they don’t say a lot about me at all.

I like what you write.

Enjoyed this post very much..Dad has been gone a whole decade now. Mom is here but her amazing story would tell you she is here by the grace of God. Now as I reach a half century old this coming March and have one adorable grandson. I have come to realize the family heirlooms need to be gathered in a box, so my two adult children will realize who their grandparents and their mother were, thank you for your thoughts.

Mathew, I’m sorry you’ve lost the conversation with your parents. That has to leave an emptiness that will never be filled again. On the other hand, what a wonderful legacy and great memories they have left you and your brother and sisters. They have given you all a splendid gift of all the knowledge and emotions in those books, something that can never be taken away.

Loved reading this beautiful expression of living, discovering, of looking back and forward, as we move on, with stories told and untold. 🙂

What a title and then how dare you proceed as sagely, “to be in an empty house lined with shelves is to be in a library of lost conversations…”. I love it

“So you heard it too, I think to myself. You understood the music that moved me so.” What an amazing way you captured the intimacy of sharing books especially as part of the lives we share with out parents. I hope my son looks at my bookshelf this way someday.

Amazing observation… Indeed, what we surround ourselves with in our homes can speak volumes about who we are. While I am sorry for your loss, your essay paints a lovely picture of the memories these books hold for you of your parents. It makes me glad to think that they will live on for you in this way. 🙂

As someone who enters a house and immediately checks out the bookcases, I can relate to your story. It is sad how each generation seems compelled to neglect their personal history until it is too late. Why do we do that? Great piece.

This is such a beautiful piece

Great description. Congrats and thanks.

“So to be in an empty house lined with shelves is to be in a library of lost conversations with them.” Such a haunting yet warming quote personifying death and home. I do like it! Your post about the thread that bound you and your parents is perfection. I am there with you, walking the halls of your parent’s home fingering the books they once read.

Beautiful and sad. A treasured connection between you and your parents that I know so many wish they had.

Brilliantly written. We can learn so much about people from the things they enjoyed in life, like the books they read, for example. Even if these people are the closest to our hearts, we can still dig up things about them we could never even imagine, and in learning more about them, we gain appreciation for what they brought into our lives. A library of lost conversation… I can’t think of a better way to put it.

I just lost my mum, and my dad is slowly moving through a house that feels empty to him. He is, in his words, putting his affairs in order. It’s the first time I’ve experienced loss at this level and I know it won’t be long before his conversations are lost too. Coming from a childhood of books and my own house also full of books, your post resonated beautifully. Thank you x

Going through my Aunt’s belongings in the run up to Christmas – she died towards the end of November – was one of the most stressful and heartbreaking things I’ve ever had to do. It was two fold, a lot of her possessions were my Nan’s, so when she died in 2010 we knew a lot of the history and memories would be preserved when my Aunt took ownership.

Six years later and as a family we were confronted with the exact same situation you were faced with – the LP situation, the photos, everything. The ghost of a future unlived ring true too – she should have had at least another 15 years but now, here we are, sifting through 66 years of life in a matter of weeks.

As a historian too I kick myself for not asking her more about family history – who is that in that photograph? Where are all the relatives buried in India? All that knowledge which my Aunt was the last of the people to know – gone.

It’s also interesting to see how people react to your personal bereavement, what’s your experience been Matt? I’ve had it range from unshakable support to ‘people die, get over it’. Considering I run a blog about Cemeteries, the last statement is a peculiar one to say – but there we are.

Sorry for the blog post response but this subject really lit something for me.

Hi Sheldon. I’m so sorry to hear about your aunt – that sounds very distressing. And you’re right: it feels strange to have all this indecipherable history in our hands – letters, photos, and so on – from which I think it’s now impossible to reconstruct much truth. I feel guilty about that – as a historian as much as a son.

People have been very supportive.

Best wishes to you & yours, Mathew

I always thought guilt was such an odd feeling in the context of mourning. I live a few time zones away from my father, so when my mother died, I rushed home and absolutely wanted to get all her stuff out of the house as fast as possible, so that my dad would not have to do it on his own later, when I wouldn’t be there. That was the truth, it was important to me, not so much to him. Then, there was the guilt of leaving him alone when I had to go back to my life many time zones away… he since found love again so all’s well on that part.

However, it’s your guilt as a historian and a son that concerns me: isn’t sharing a two-way street? I also asked countless times my grand mother back then to tell me more stories, to feed me the past so I’d remember it. But she was never really interested in telling the stories. Same as asking my parents how they met, it was like pulling their teeth… I have a general story and that’s it. Why they were never interested in painting me an epic picture will remain one of my life’s great unanswered questions. I must make my peace with it.

I am truly sorry for your loss, hang in there. Hopefully you’ll be able to feed your children one day with your own stories so that your legend endures.

Love this Mathew, resonates with me. A year or so after my father died, I helped my mother pack up our childhood home. We took some heavy boxes to the local charity shops, and taped up others ready to come to her new home round the corner from me. We even took down some bookshelves dad had put up 50 years before, to rehouse her books here. On the wall dad had used shelf fixings with in-built ‘self leveller’ spirit level bubbles. One bubble was slightly off-centre. Against it he had written, ‘inaccurate self-leveller’. Even the shelves hid long-past conversations…

You lovely man. That was quite beautiful.

Very perfect.